Preventing Food Loss in the Banana Trade Supply Chain in the Philippines

Bananas are among the most popular fruits in the Philippines because they are available fresh all year-round, and they are generally much cheaper than other tropical fruits. The banana trade in the Philippines is also a booming business. Around 64% of production is consumed locally and the other 34% is exported to top buyers including Europe, USA, Japan, China, and Canada.

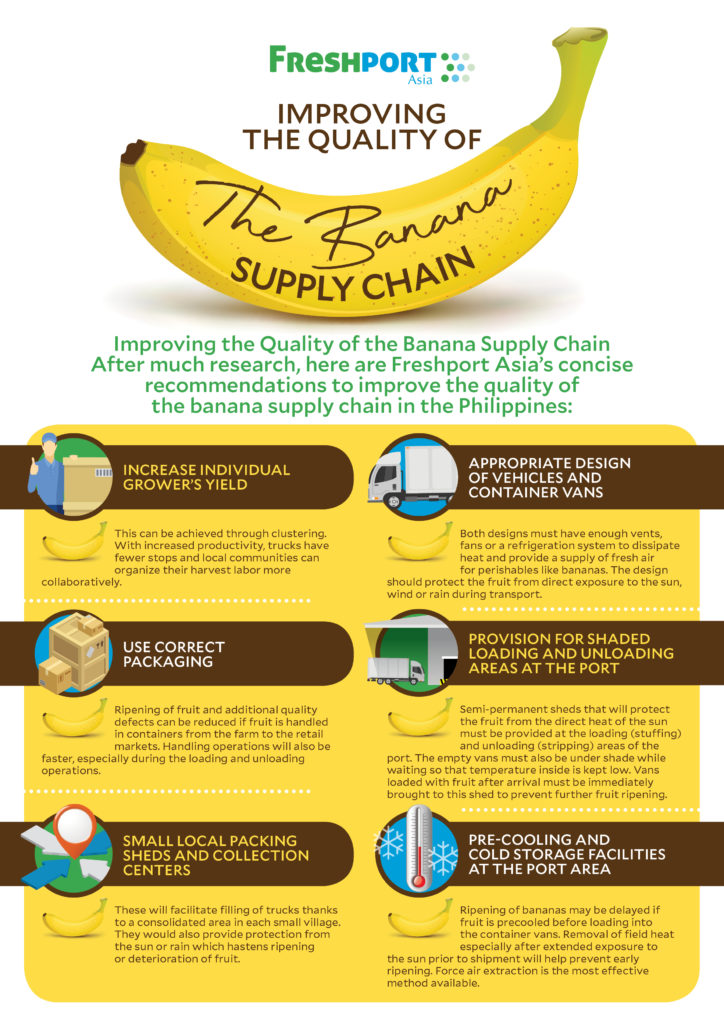

(Check Down Below for an Informative Infographic!)

The Philippines is the second largest exporter of bananas after Ecuador, and in 2015 the country produced nearly 9.1m tons of bananas, with Cavendish cultivars accounting for about 50% of national banana production, Saba at 29% and Lakatan at 11%.

The volume of banana production in the Philippines is steadily increasing and went up by 3.1 % from 2.33 million tons for October-December 2016 to 2.41 million tons during the same period of 2017 (data from the Philippine Statistics Authority).

The increase can be attributed to the expansion of established banana plantations, and to bigger sizes of bananas resulting from less weather disturbances in some cultivation areas. The increase can also be attributed to the bigger bunches harvested from the banana farms which have applied newer technologies and better inputs to improve their production.

However, although the growth of the banana trade is continuing to increase, there is still much waste throughout the supply chain. Join us as we explore the current state of the supply chain and from the information gathered, we make several recommendations for further improvements.

Post-Harvest Issues

A majority of local banana varieties in Philippines are harvested green and are used for cooking. The opposite is true of exported varieties in international markets where fully ripe bananas are in demand. Because of this fact, traders will then often take green bananas and use calcium carbide tablets to produce ethylene in an effort to quickly ripen bananas. This isn’t proper handling and there are many other post-harvest concerns in the current supply chain. The post-harvest characteristics that need to be taken into consideration and affect the life of the banana the most is that bananas lose water, are prone to decay, are prone to injury, and do not fare well when being refrigerated.

The potential quality of bananas is established at harvest and is largely determined by the stage of fruit maturity at which time the banana is harvested, as well as the method used to harvest the banana. Bananas harvested at full maturity will develop good peel and pulp color, with full aroma and flavor at the ripe stage. Fruits harvested at an immature stage are often of poor quality upon ripening. While harvesting at an advanced stage of maturity produces many desirable qualities, it may be unsuitable for long distance shipment since ripening will occur during shipment and result in fruit having a shorter shelf life. Nearly all local varieties of banana in Caraga are harvested at either light three quarters or full three quarters to ensure maximum shelf life. Good post-harvest handling practices are important in maintaining the quality and assuring the safety of the fruit as it moves through the supply chain from producer to consumer. Currently, over-ripening and mechanical damage caused by bruising and compression are the main causes of losses in banana supply chains.

To curb this, bananas are often harvested green in order to reduce damage in transit and are artificially ripened prior to being displayed on retail shelves. Once harvested, a banana is subject to continued change until it completely deteriorates. The ripening process impacts a banana’s appearance, flavor, texture and nutritive value, and that cause it to age and subsequently to rot and decay.

While some ripening changes are desirable such as sweetness, many bring about quality deterioration such as softening allowing them to be more easily damaged. These post-harvest changes cannot be stopped but can be slowed down through good post-harvest management practice. While there are a number of factors, harvest maturity is at the heart of this push and pull on the quality of the bananas. A more mature fruit means better taste and quality, while harvesting a less mature fruit means protection against handling damage.

Protecting Quality

Beyond just the ripeness at time of harvest, there are numerous other factors to consider in protecting the fruit throughout the supply chain.

For example, bananas are susceptible to attack by insects and decay-causing organisms that can promote the rapid deterioration of bananas. Rough handling of bananas can create wounds that could serve as entry points for microorganisms. Bananas that come into direct contact with the soil or unsanitary market floors are susceptible to microbial contamination which could pose a food safety risk and lead to illness in humans when consumed.

Bananas are also highly susceptible to injury during handling. Rough handling particularly during transport and market handling leads to damage. Once damaged, all of the biological processes of the banana – such as respiration and ethylene production – proceed at a very rapid rate leading to rapid deterioration of the quality of the fruit.

When harvested, bananas can no longer replace the water that is lost from the peel. Therefore, they are subject to shriveling and weight loss resulting in a loss in their marketable weight and their visual quality if stored under conditions of low humidity. The moisture content of the fruit must be maintained in order to retain the desired quality.

For plantation harvests, bananas are often kept out of the sun in sheds waiting for water spaying and water bath immersion prior to packaging. Additionally, packing in plastic bags for boxing maintains high moisture content and controls respiration during transit.

For small scale producers, banana leaves are often put on top and stems on the side and underneath to protect bunches and hands (when cut) on open trucks. Unfortunately loading is in the open

into containers where the use of block ice has two purposes. Stabilize temperature in the container and to keep the humidity high in the containers during shipment.

Modern Trade

Throughout the small-scale farm banana chain there is a lack of capital, insufficient infrastructure and lack of synchronization between players. Food loss is not seen as an issue as nearly all direct and indirect products have a use or salable value. From farm to port, bananas are subject to heat, over-stacking on trucks, with little or no facilities to grade and pack into containers. The main cause of value loss is for product during transit is overripening and softening of fruit or when ships are delayed from sailing due to bad weather.

Informal discussions with local modern trade retailers on the front and back end margins revealed that bananas are often seen by many retailers as a loss leader or anchor product used to sell in other fresh products.

Similarly, the producers net share and wholesalers’ margins also decrease substantially when shifting from green (un-ripe) bananas to ripe table fruit. The co-operative marketing of green and yellow bananas is a more efficient system in terms of both operations and price. Marketing cost has been identified as the major constraint in the wholesale marketing channel and bringing down the costs, particularly the commission charges as demonstrated in the co-operative channel, will help in reducing the price-spread and increasing the producers margin.

Inter-Island Banana Handling Recommendations

Here are a number of recommendations to improve the quality of the banana supply chain in the Philippines:

• Increase the Individual Grower’s Yield. This can be achieved through clustering. With increased productivity, agents and assemblers could fill their truck with fewer stops and local communities could organize their harvest labor more collaboratively.

• Use of Logistics Packaging Containers. Ripening of fruit and additional quality defects can be reduced if the fruit was handled in containers from the farm to the retail markets, such as is the case of ‘Lakatan’ bananas from other regions of the country. Handling operations will be faster, especially during the loading and unloading operations. The use of bulk bins with 200-500 kg capacity may be an alternative to bulk-loading, small cheap foot operated pallet lifter can be used.

• Small Local Packing Sheds or Collection Centers. These will facilitate filling of trucks since the vehicle would not have to go to every grower’s property in the area but consolidated in each small village or cluster. They would also provide protection from the sun or rain which hastens ripening or deterioration of fruit. The shed or center would also provide a community meeting point and storage place to delay the ripening of fruit if harvested earlier.

• Appropriate Design of Vehicles and Container Vans. Both designs must have enough vents, fans or a refrigeration system to dissipate heat and provide a supply of fresh air for perishables like banana. The design should protect the fruit from direct exposure to the sun, wind or rain during transport. Some provision must be made for dividers to reduce the compression on bulk-loaded fruit.

• Liability of Shipping Companies. Time is of great essence during ambient transport of bananas due to ripening and product deterioration. A delay in loading or unloading of just a few hours may mean huge losses. Provision for heat exhaust fans is not a standard accessory on local shipping vessels since it is mainly for passengers. Temperature monitoring in the area where the fruit vans are located is usually not done. From the traders’ experience, the shipping lines have no liability if their schedule is delayed, if containers were placed near the ship’s engine or vans were exposed under the sun for several hours. Or bad weather delayed the departure of the ferry – then it has the potential for total consignment loss. Additionally, there has been a significantly higher incidence of ferry accidents and total loss at sea. Some degree of accountability is required.

• Provision for Shaded Loading and Unloading Areas at the Port. Semi-permanent sheds that will protect the fruit from the direct heat of the sun must be provided at the loading (stuffing) and unloading (stripping) areas of the port. The empty vans must also be under shade while waiting to be loaded with fruit so that temperature inside prior to fruit loading is kept low. Vans loaded with fruit after arrival must be immediately brought to this shed to prevent further fruit ripening. An existing facility has been built – but poorly located and faces issues in activating. The Department of Agriculture, the shipping lines and port authorities can work hand-in-hand to establish this facility.

• Pre-Cooling and Cold Storage Facilities at the Port Area. Ripening of bananas may be delayed if fruit is precooled before loading into the container vans. Removal of field heat especially after extended exposure to the sun prior to shipment will help prevent early ripening. In case of delays associated with the ship’s arrival or departure, or occurrence of typhoons, fruit may be temporarily kept at low temperatures to prevent its early ripening. This facility may also be offered to other perishables that are regularly shipped to Manila and Cebu. Force air extraction is the most effective method available.

• More Information Dissemination. Despite numerous dialogues and seminars have been conducted on the past, some key players still lack basic knowledge on the proper handling of bananas, because of the fast turnover of port and shipping lines staff. Measures to mitigate ripening problems are by trial and error and through experience. A more comprehensive educational program for stakeholders must be implemented.

*This study was undertaken in conjunction with CEL Consulting on engagement through Winrock International sponsored by the USDA, under the Philippine Cold Chain Project.

**A special thanks to Mathilde Thuy Tran Van for all of her help in this joint project

Credits:

http://www.fao.org/3/I8242EN/i8242en.pdf

http://ucce.ucdavis.edu/files/datastore/234-1576.pdf

Write a Comment